Matthias Bastian is an online journalist and editor of the leading international XR magazine MIXED. Since 2015, he has been reporting intensively on augmented reality and its benefits for industry and the private sector.

Key Takeaways

- Augmented reality uses a combination of hardware and software to digitally enhance a user’s view of their physical surroundings.

- Different kinds of hardware enable different levels of AR experience ranging from simple apps on mobile phones to complex processes on dedicated headsets and glasses.

- Remote collaboration, interactive 3D design, and impactful simulations are only a few of the uses for AR across multiple industries.

Augmented reality (AR) is generating a lot of buzz in gaming and social media. As exciting as it is in those fields, it has more varied and more practical use cases in fields like manufacturing, education, and medicine. But what is AR, exactly?

What Is Augmented Reality?

AR is any technology that overlays digital elements over a user’s natural field of view. In consumer use cases, these digital elements are usually game elements or visual effects. In “industrial augmented reality,” these digital elements typically provide contextual information to the user or otherwise annotate their physical surroundings.

AR enhances the real world with digital information.

This information can be manually entered into a program by the user or collaborator, but information is increasingly coming automatically from other connected devices like smart sensors. In some cases, the information is generated by the AR application itself as it recognizes items or images in the environment or collects its own information through connected sensors.

The most basic AR applications simply present pre-selected media or even other applications in a more convenient form factor. For example, AR glasses can provide “virtual screens” allowing users a hands-free heads-up way to participate in video calls, check messages, watch videos, or play games.

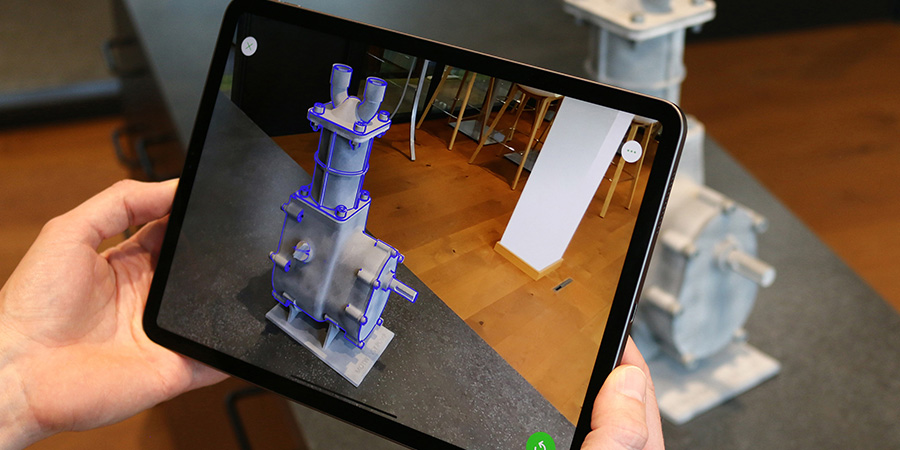

More advanced AR applications offer greater immersion by scanning the environment in real time and placing 3D objects in it with correct perspective and scale. For example, machines can be covered with precisely fitting digital overlays, or prototypes of new products can be projected into the room in real-time, full-scale 3D for collaborative work.

How Does AR Work?

Augmented reality hardware can take the form of bulky headsets, specialized sunglasses, or even a standard mobile phone.

AR devices typically consist of a translucent screen that the user looks through as it displays applications, a transparent screen onto which an application is projected, or an opaque screen that displays a live video feed of the user’s surroundings augmented with digital elements. This last system, called "passthrough," is the most common because it's how AR works on smartphones and tablets, which remain the most common AR devices. Passthrough refers to the built-in camera that passes a video image of the real world to the device's display.

Not all AR applications will work on all devices. Even most relatively simple AR applications require an understanding of depth, which helps them place digital elements so that they appear to be in the user's environment, not just in front of the user's eyes. Smartphones are getting better at recognizing depth based on video feeds. AR glasses typically have two spaced cameras or a depth sensor that work together to understand depth.

More advanced AR applications require still more hardware and software affordances including the ability to connect to the Internet and communicate with other smart devices to display information from things like environmental sensors. Other AR applications generate their own information about the world through more advanced software like image and object recognition.

Augmented Reality vs. Virtual Reality vs. Mixed Reality

We understand that augmented reality means that the natural view of the environment is altered with but not replaced by digital elements. How does this differ from the other forms of “digital realities” that are out there?

In Virtual Reality (VR), the entire view provided by the device is generated by computers. It may resemble real, physical environments and may include representations of other real, physical people, but the entire virtual scene replaces the user’s entire natural view. VR severely limits situational awareness so use of VR in industry is largely limited to simulations, modeling, training and a few other roles in which the real world doesn't need to be involved.

In mixed reality, AR, VR, and video call users can collaborate in the same space.

Mixed Reality (MR) is a spectrum including augmented reality, virtual reality, and a few other niche display technologies. This definition goes back to the Reality–virtuality continuum by Paul Milgram. A mixed reality device is one that offers both VR and AR. Examples include Meta's Quest Pro or HTC's Vive Elite XR, which can handle pure VR but also offer high-quality AR through the camera passthrough.

What are the benefits of AR?

The benefits of augmented reality depend upon its implementation. We’ve already touched on several benefits including contextual information and a heads-up, hands-free interface.

However, not even these benefits are universal among AR use cases. An AR app running on a smartphone can provide contextual information, but it isn’t heads-up or hands-free. A pair of AR glasses displaying virtual screens might be heads-up and hands-free, but it might not be displaying information dependent on the user’s environment.

One of the greatest universal benefits of immersive AR is the precise placement of 3D digital objects in reality. With AR, you can interact with digital objects just as you would in the real world, touching them, walking around them, and viewing them from different perspectives. This makes AR the most natural computer interface.

AR Technology

While we might discuss an AR app or a pair of AR glasses, a complete AR system is never just a piece of hardware or just a piece of software. A complete AR system consists of hardware, software, and the user interface with each of these consisting of several individual components.

Hardware

AR hardware refers to the physical components that enable a given AR application. These generally consist of the display, the computer, and sensors.

We’ve already discussed the different kinds of displays, including passthrough. Screens that a user looks through are actually similar to a much smaller version of the technology behind television and computer screens. The third option is the “waveguide” display which itself consists of a “light engine” that projects the digital elements, and the lens onto which they are projected.

The displays are powered by a computer to run the application. In some cases, this is housed entirely within the frame of a pair of AR glasses. To reduce the size of AR glasses, much of the computing happens on a paired device – either a smartphone or a “compute box,” or “puck,” worn on the body. This external computer may connect with a hard-wire, or a Bluetooth or Wi-Fi connection.

Microsoft's HoloLens AR headset is the most widely used in industrial applications.

AR devices also need at least one sensor, a camera, to help them understand the environment. More advanced AR glasses often have multiple cameras. These cameras may do things like detect different wavelengths of light both for scene understanding and to give different viewing powers to the wearer. There are also modular accessories that can display heat maps and other information.

Software

More robust AR applications require some specialized programs that help to display digital elements in the real world and add value to the user. These can include recognition and tracking, localization and mapping, and spatial anchors.

Most advanced AR devices build experiences around Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) technology. This allows the device to gain a dynamic understanding of the user’s immediate surroundings so that digital elements can be placed in the environment or even generated by the environment in ways that make sense to the viewer.

Object and image recognition refers to the ability of a device to understand specific elements within that environment. Object recognition usually allows the application to display information specific to that object, while image recognition typically allows it to display information not otherwise triggered by the environment by scanning an image – similar to following a link in text.

Tracking allows the application to understand an object’s position and orientation in space. This can allow more powerful applications to run in more dynamic environments but it is also the basis for some emerging user interfaces.

Visual tracking has come a long way in the last few years.

While object and image recognition allow an application to present information based on the environment, spatial AR allows users to place digital elements into the AR view of the environment. These can include models, notes, or other kinds of annotations that remain “anchored” to that position in space for their future reference and often for other users as well.

User Interface

Several new user interfaces are being explored to maximize the potential and practicality of these devices and applications. AR both enables and to some degree requires new user interfaces designed for working with 3D content.

The easiest and often the most user-friendly way to interact with an AR app or device is through a familiar device like a smartphone’s touchscreen. This is also handy because many AR devices get their power and computing capabilities from a connected device anyway. Unfortunately, this method can be impractical for users that need their hands to do other functions.

Many AR glasses have simple controls built into the frames. These allow one-handed interactions that are often intuitive and easy to learn without requiring the user to interact with a connected device. However, these controls are often less nuanced than other user interface methods.

Tracking technology allows many AR glasses to work with gesture controls allowing the user to manipulate virtual elements in their view with their hands. Because this replicates the ways in which we are used to interacting with physical objects, this input method is the most intuitive and nuanced user interface option and is very handy in situations like modeling and design.

Gesture controls for AR applications are often intuitive and engaging, but require both hands to be free, limiting their practical use cases.

Many industrial AR applications and devices use voice controls. These controls allow the user to interact with devices and applications while keeping their eyes and hands on the job. While one might think that this interface would be challenging in loud environments, microphones and microphone placement can effectively isolate the user’s voice from noise in the environment.

Development

Every component and aspect of augmented reality technology is rapidly improving. The field-of-view for displays is getting bigger while the necessary energy expenditure is getting smaller. Displays are also getting brighter, which makes them easier to use in bright environments. The sizes and energy requirements of display and computing hardware are also decreasing. This allows for more comfortable form factors with longer battery life and more powerful applications.

Connectivity is also improving, which improves experience performance even with wireless connections to remote computers. Advancements like cloud and edge computing also give AR glasses faster access to more computing power while reducing the demand for memory space, computing, and rendering on the devices themselves. In the future, this could lead to smaller, more compact headsets that are ideal for everyday, all-day use.

The ways in which people create applications are also becoming more powerful. New toolsets are appearing all the time that give low- or no-code users the ability to create their own AR applications through more intuitive interfaces. Businesses can now build their own AR applications with drag-and-drop ease, rather than investing in costly development from scratch each time.

The creation of 3D assets is also becoming increasingly accessible with most modern smartphones having the capability to create models and maps from physical objects and places.

AR Use Cases

It is hard to think of a single industry that doesn’t stand to benefit from using augmented reality. However, how and where different industries can best use the technology can differ widely.

Industrial Manufacturing

From training to the assembly line, to packing and shipping, different kinds of AR applications can be used by just about everyone in a manufacturing division for just about any product. Using emerging technologies throughout the development, manufacture, and service of a product can help to create a “digital thread” that connects the physical and digital strengths of a product throughout and beyond its use.

-

Training

Industrial manufacturing jobs may only require an individual to do one specific task. However, doing that task perfectly every time is crucial for a consistent product and a safe environment. Hands-on-training is a necessary part of the process but can mean harrowing first moments with real products and workers on the line.

Augmented reality can be used to simulate complex situations in a convincing way in the real, physical workplace environment with the actual tools that the worker will be using on the job. AR devices and applications that record processes carried out by experienced workers can also be used to transfer knowledge on to newer workers.

Augmented reality can give workers access to additional input and information by adding contextual annotation to their view of the environment.

-

Assembly

Augmented reality can also be used to provide guided instructions for learning new scenarios, refreshing old scenarios, and handling the situation when things don’t go as planned. While some work processes may be automated, AR is increasingly being used for remote assistance as well.

The cameras on the outside of an AR device can show a remote expert exactly what the worker is seeing as they see it. Through the AR device, the user can see and hear the remote expert, as well as see annotations that the remote expert places in the user’s environment in real time.

-

Monitoring and Visualization

Assembly line workers aren’t the only people on the manufacturing floor. Someone also needs to make sure that the machines are running as they are supposed to, as a machine going down can mean a dangerous environment and/or lost time and products.

Information from sensors and programs in the machines themselves can be visualized within AR applications and devices in a visible “digital twin” of the facility. In addition to making this information more accessible and intuitive, many applications involve direct remote programming of machines in this digital twin all from within an AR application for maximum safety and efficiency.

-

Operations and Commissioning

The digital twin can be used to maximize the efficiency of a manufacturing floor, as well as for more seamlessly automating some processes. This can help supervisors and teams to set up machinery and equipment and to keep them running at peak efficiency during normal operations, as well as help them to manage more challenging operational tasks like line-changeover.

-

Quality Control

Between the assembly line and packaging, products can be visually inspected with AR applications. A digital model of the ideal product can aid in visual inspection. More than that, object recognition, machine learning, and sensors on the outside of the AR device can work together to detect flaws and abnormalities in the finished product that might have escaped the naked eye.

Service, Maintenance, and Repair

The benefits described don’t have to stop when a product leaves the factory floor. That is handy considering the people responsible for servicing, maintaining and repairing that product in the field probably aren’t the same people that built it. Work processes, service orders, remote assistance, and annotated virtual models can be made available to frontline workers, increasing their efficiency, often using the same applications.

In some cases, companies make AR applications available to customers as well. While typically not as full-featured as those used on the production site, they can allow customer self-service under the guidance of an expert.

Mapping and Navigation

Software similar to that which allows an AR device to understand the user’s surroundings can also be used to make a spatial recording of those surroundings. Mapping a space in this way can be used to optimize floor plans, simulate emergency scenarios, create virtual training and orientation applications, and more.

When a place has been mapped, spatial anchors, image recognition, and other AR tools can also be used to create heads-up wayfinding applications. These applications can help staff and visitors alike easily find their way through any institution operating a large campus, including manufacturing facilities, hospitals, schools, hotels, and recreational facilities.

AR can help you find your way by putting directions right in your field of view.

These applications can also contribute user data back to the program, helping site managers understand how people navigate these spaces. This information can then be used to optimize floor plans or, depending on the use case, inspire more AR applications, products, or services.

Remote Collaboration with AR

In addition to remote assistance and see-as-I-see video sharing, AR can enable remote assistance in a number of use cases. These include standard video calls displayed within AR glasses. Models created during the design process can also be worked on by remote teams seeing the same virtual model in their design space, as well as virtual representations of their remote coworkers.

AR Adoption by Industry

Manufacturing is likely one of the largest industries in terms of current AR adoption. However, it is by no means the only industry utilizing AR.

Education

Remote collaboration use cases can easily be applied to education for things like immersive remote classes. These classes can center around interactive virtual models that students can study alone, in a shared physical space, or with remote learners and instructors.

While full-featured AR headsets are often too expensive for many students and schools to invest in, even more basic AR applications running on smartphones and tablets have a lot of promise. Some applications generate 3D models from flat images in conventional textbooks. Others recognize objects in the world to help students learn new words or pull up information on plants and animals around them.

Through mobile phones, students can access the benefits of AR without investing in an expensive headset.

Electronics and High Tech

Anyone who uses a computer or smartphone for work has the potential to benefit from AR. Some of the simplest AR applications involve “screen mirroring” – displaying applications from a smartphone or computer within an AR application.

One virtual screen can be handy, but some applications allow multiple virtual screens to be positioned around a user and temporarily positioned or permanently anchored in their physical environment. Instead of one or two monitors, how about four or five? That’s regardless of the size of your physical desk. In fact, you don’t even need to be at your physical desk. Your virtual office can be anywhere.

Automotive

Automotive, as an industry, runs the gamut from design and manufacturing, into retail, to service and repair. So, just about every use case for AR applies to automotive during any given product cycle.

Starting with design, team members can work together on remote models. That includes conceptual designs of the whole car as well as AR CAD models of individual parts and systems. What’s even better is these virtual models can then be “represented” in AR applications down the line.

The virtual model of a part or system can be used to train new workers. They can be the standard against which physical parts are checked during manufacturing and quality control. Virtual models can also be used in virtual show rooms and configurators that allow customers to get an immersive and interactive look at digital floor models often without needing to leave their homes.

Augmented reality solutions can give consumers many of the same insights and abilities that workers enjoy from more complex applications.

Retail

Vehicle showrooms are just one example of how AR can play a role in retail. Virtual models of just about anything can help prospective buyers envision a physical item in their surroundings. It can also be used to introduce and familiarize products with buyers before and just after a product becomes available.

AR is often used in interior design to help shoppers envision exactly how a fixture might fit in their homes, or how a room might look in a different color of paint. AR is also increasingly being used in fashion retail in virtual try-on experiences that let customers envision themselves wearing jewelry, clothing items, makeup palettes, and more.

An AR activation doesn’t even need to become a physical reality or drive a physical purchase to be successful. Consumer-facing AR activations can be a powerful tool for building brand recognition and driving engagement.

Life Sciences

Just like there can be virtual models of car parts and virtual twins of assembly lines, interactive models of biological systems and virtual representations of living people are increasingly allowing healthcare providers to better understand patients, better diagnose and treat medical conditions, and learn and even perform medical procedures.

That’s to say nothing of the other benefits that life science professionals can gain from the application of AR in education, remote collaboration, and other areas.

Rolling Out Industrial AR

Augmented reality can come in many different forms on many different devices. Different applications can help different users achieve different goals. Finding how and where it best fits into any given scenario is still a learning experience for many organizations but it’s getting easier as the technology continues to develop and improve.

To learn more about how to implement AR in your industry and select the right AR solutions for your use case, check out the Industrial Augmented Reality Buyer's Guide.